While I thoroughly enjoyed The Dark Knight Rises, one of the more negative reviews I’ve read has stuck in my mind. The review was by Jeffrey Overstreet, an incredibly thoughtful Christian whose reviews are more than a tally list of profanity and sex scenes (as a side note, I’d highly recommend his book Through a Screen Darkly if you are interested in the intersection of faith and film). Overstreet’s conclusion have been the words I cannot shake:

His [Batman’s] revolution is achieved with violence rather than love. And it achieves only postponements of destruction, not the defeat of death itself.

When the end credits rolled, Keuss’s [a theologian that saw the film with Overstreet] first observation was this: “We still believe that Judas was right.”

Indeed. As the cheering crowd made clear, the savior we’ll celebrate is the one who puts on the best fireworks show, who unleashes hell against those we have judged, who gives the rest of the guilty Gothamites another day to revel, the wages of their sins postponed and forgotten until another supervillain emerges.

The cycle of violence will continue. The rich and heartless will remain rich and heartless. The middle class will stay angry and covetous. The poor will remain neglected.

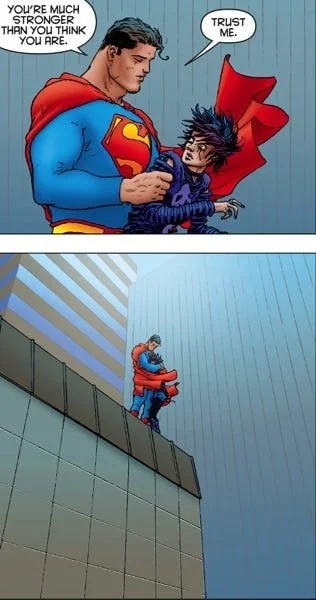

I don’t know if I entirely agree with Overstreet’s take on the Dark Knight, but I do have a blind spot for comic book-based superheroics. Yet that quote—“We still believe that Judas was right”—has haunted me.

A little background on that quote. A common interpretation for the reason that Judas betrayed Jesus—outside of “the devil made him do it”—is that the disciple was incredibly disillusioned when it turned out this man he thought was the Messiah was not going to overthrow Rome. Rather Jesus was saying he was going to die at the hands of these vile oppressors. Military uprising is how kingdoms were established, so how was this so-called Messiah going to establish a kingdom by dying and not violently overthrowing the opposition? Angered at a seeming betrayal of Israel, hoping to force Jesus’ hand, or for whatever other reason, Judas handed his teacher over to be executed. That’s an abridged version and people far smarter than I could give you better commentary than that.

Now no person is ever going to say that Judas was right, but Overstreet’s friend suggests something that is likely more true than we’d want to admit: our actions speak to us believing in change that comes from a fallen humanity’s expressions of power than the life-changing, self-sacrificial, loving kingdom work of Jesus.

The reason that statement is so unnerving is that it is true when you look back at our church history. Think about the ways in which Christians have tried to change the world for God. From the horribly violent Crusades to the ugly marriage of faith and politics in the last several decades, these are not the ways of the kingdom that Jesus was announcing. What did those things accomplish? Violent counterattacks and the perpetuation of a destructive cycle.

If you walk away from those more dramatic examples and simply look at how we often respond to conflict online, you’ll see us often respond by getting angry and dehumanizing those with whom we disagree. Our shared pictures, status updates, tweets, and comments often assent that we think Judas was right. We believe the way to defeat the “enemy” is through belittling, hurting, and destroying the opposition. We forget that Jesus told us to love our enemies.

This is not to say we should not enjoy superhero movies or vote or even criticize those things that we find to be awry in the world. But we must remember that Judas was not right. Power and violence in whatever forms it takes may get short-term results but it doesn’t truly change anything. So you, I, and everyone else must be careful of what we celebrate and of how we live.